Nth Generation Idahoans

How much does birthplace matter in political debates?

My ancestry is about as American as it gets. My earliest documented forefather to come to the New World was Thomas Morris—my 9th-great-grandfather—who sailed for New England in 1633 and signed the charter creating Hartford, Connecticut. The entirety of my maternal line was in North America before the War for Independence. Many on the other half arrived from Germany and Wales between 1840 and 1890.

I believe this gives me a real stake in the United States of America. My forefathers put their blood, sweat, and tears into forging this country, and I feel an obligation to preserve it for my posterity.

Men once held their home states in higher regard than their nation. Following the Battle of Fort Sumter, when President Abraham Lincoln called for volunteer troops to suppress what he considered a rebellion of southern states, Robert E. Lee remained loyal to Virginia.

What does that mean for us today? I often see political debates in Idaho devolve into complaints about out-of-staters trying to upend longstanding traditions. A person’s place of birth, or how far back their family can trace its lineage, too often becomes a substitute for real policy debate.

Ironically, some of the same voices that insist a newly arrived refugee is just as American as me also argue that, as a transplant to Idaho, my voice should matter less. Go figure.

The truth is that heritage does matter in many ways. If your family settled this land before statehood, and you can point to five generations of ancestors buried in the same ground, that is an incredible connection. My ancestry, however, is one of constant migration—from Scotland to Ireland to New England to the Midwest, and finally to the West Coast. My hope is that by settling here in Idaho, I will end that pattern for my children and their children.

I recognize that I don’t have the Idaho heritage of many others, and that’s fine. I’ve worked hard to be respectful of those who have lived here their whole lives—whose 5th-great-grandfathers tilled the soil in the wilderness, or even of the Native American tribes whose ancestors roamed these lands for countless centuries. I still have much to learn about the history and traditions of this place.

Yet I also believe I have something to add to the conversation. Like many transplants, I have seen firsthand what left-wing policies inevitably do to once-great states. Data shows that most people moving from California, Oregon, and Washington are not liberals bringing liberalism to Idaho, but conservative refugees warning of the road to Hell that is paved with the best intentions.

My ancestors may not have lived in Idaho, but God willing, my descendants will. That gives me a stake in the future of this great state as well.

Many influential Idahoans were not born here. Sen. William Borah, “the Lion of Idaho,” whose filibuster helped defeat President Woodrow Wilson’s plan to join the League of Nations, was born in Illinois and came to Idaho by train just after statehood. Gov. Robert Smylie, who once held the record as Idaho’s longest-serving governor, was born in Iowa. Other governors were born out of state as well, such as Cecil Andrus from Oregon and Dirk Kempthorne of California.

The same is true regarding some of today’s most influential political leaders. Sen. Jim Risch, who served as state senator, lieutenant governor, governor, and now U.S. senator, was born in Wisconsin. Attorney General Raúl Labrador was born in Puerto Rico. Idaho GOP chair Dorothy Moon was born in Missouri, and Boise mayor Lauren McLean hails from Massachusetts.

Of course, many political figures were born in Idaho, and that’s certainly something to celebrate. It’s good for people to preserve the society their ancestors helped shape. For example, Gov. Brad Little has a tremendous Idaho heritage: his grandfather Andrew emigrated to the Idaho Territory in 1884 with two dogs and $25. By 1935 he was known as the “Sheep King of Idaho,” and his family continues to ranch here today.

What a legacy!

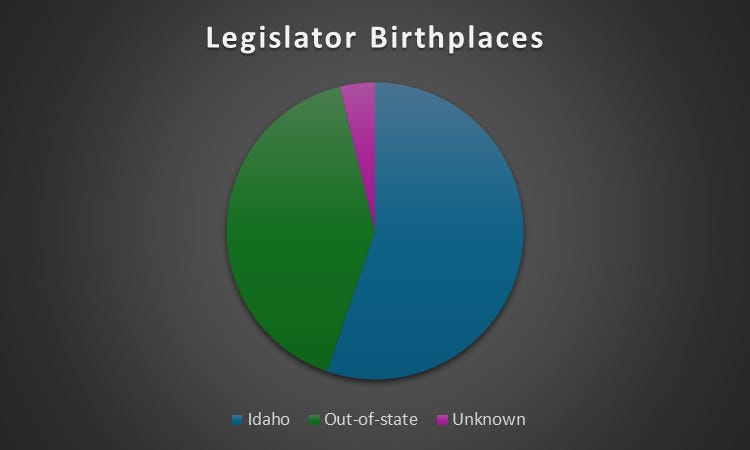

As an experiment, I collected as much data as I could on the birthplaces of current Idaho legislators. While I couldn’t find information for a few, the results were enough for a quick analysis. Of the 105 lawmakers in the House and Senate, about 55% were definitely born in the Gem State. 41% were definitely born out of state, including House Minority Leader Rep. Ilana Rubel, who was born in Canada. The remainder were uncertain.

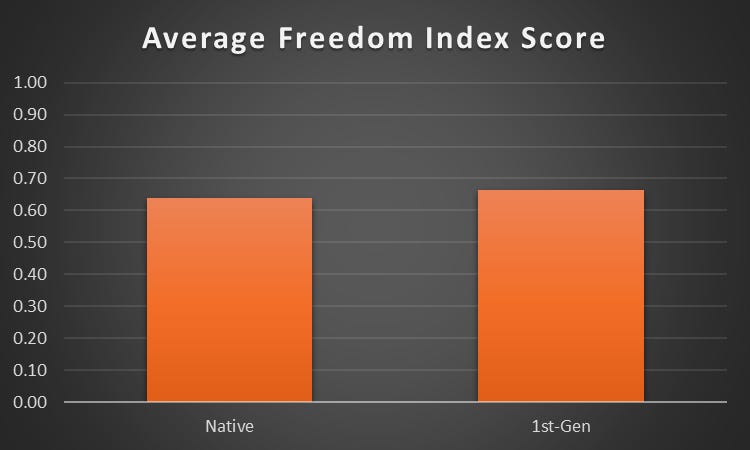

I then compared those birthplaces with legislators’ 2025 Idaho Freedom Index scores. Native Idahoans averaged 67%, while transplants averaged 64%. A difference, yes—but a very small one.

There’s nothing earth-shattering here. Neither Idaho natives nor recent transplants have a monopoly on being strong conservative defenders of freedom, nor on being moderates and progressives pushing Idaho blue. The native-versus-transplant rhetoric is ultimately a distraction from the policy debates that will shape the state our children and grandchildren inherit. It’s time to set those distractions aside and work together for our posterity. Together, we can honor those who built this great state while ensuring it remains a place our descendants will cherish well into the 22nd century.

A refreshingly interesting an informative enlightment. Thanks, Brian, from another patriot* who voted with our feet.

(*5th generation Oregonian: G-G-grandfather captained an 1853 Oregon Trail wagon train.)

Your analysis of the native-versus-transplant debate touches on something fascinating, but I think there's a deeper historical irony worth exploring—particularly regarding how some LDS Idahoans invoke their "Nth generation" status in political discussions.

While you rightly note that birthplace shouldn't be the determining factor in political legitimacy, there's a striking contradiction when members of the LDS community use deep Idaho roots as political currency, given that their ancestors were systematically excluded from Idaho's very founding as a state.

The historical record is clear: by 1882, Idaho Territory had disenfranchised LDS members through anti-polygamy laws that stripped them of basic civic rights—they couldn't vote, hold office, or even serve on juries, regardless of whether they actually practiced polygamy. This wasn't a minor footnote; it was a deliberate strategy that helped Idaho achieve statehood in 1890, earlier than Utah, precisely because it had neutered Mormon political influence.

Eastern Idaho's LDS settlements, many established in the 1860s and initially thought to be in Utah Territory, found themselves suddenly in Idaho after an 1872 survey—and then promptly disenfranchised. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld Idaho's anti-Mormon constitutional clause in 1893, three years after statehood. These communities were literally present for generations but legally excluded from the democratic process that created modern Idaho.

So when I hear descendants of these early LDS settlers invoke their multi-generational Idaho heritage as grounds for greater political authority, there's a profound irony at play. Their ancestors weren't just passive observers of Idaho's founding—they were actively excluded from it. The "Idaho heritage" being claimed was built, in part, on their systematic disenfranchisement.

This doesn't diminish the legitimate contributions LDS families have made to building Idaho over the past 130+ years, nor does it invalidate their voices in today's political conversations. But it does highlight how selective our collective memory can be when constructing political narratives around heritage and belonging.

Looking forward, this historical context raises intriguing questions about future loyalties. If circumstances ever arose where a Deseret-style nation became viable—perhaps through constitutional convention, secession movements, or federal dissolution—would Eastern Idaho's LDS communities maintain their "Idaho heritage" identity, or would their deeper religious and cultural ties pull them toward reunification with their Utah brethren? The original State of Deseret, after all, encompassed much of what became Eastern Idaho before federal authorities deliberately carved up Mormon settlement areas to prevent exactly such a "superstate." The suspicions, Civil War tensions, and outright conflicts (like the Utah War of 1857-58) that the federal government waged against the LDS prevented this natural consolidation in the 19th century. But demographic and political realities can shift dramatically over generations, and the very "heritage" claims being made today might ironically serve as the foundation for tomorrow's territorial realignments.

Perhaps this historical complexity is another argument for your broader point: that policy positions matter more than genealogy. After all, if we're going to play the heritage game, we should at least acknowledge the full, complicated story of who was and wasn't allowed to participate in creating the Idaho being inherited today.