Crime is a Policy Choice

Unchecked violence is not simply part and parcel of life in the 21st century

Is a human being in a state of nature inherently good or inherently bad? It’s a simple question, but the answer determines your worldview. If you believe people are naturally good, then you will see government—and society in general—as evil, seeking to impose dominion on free souls. On the other hand, if you agree with the traditional Christian belief that all humans are sinners, then you will see government and society as a necessary constraint on evil.

Every society in human history has grappled with the problem of evil. Whatever their professed motive, there have always been people who violated the law and harmed their neighbors. The Laws of Moses prescribed the death penalty for numerous crimes, from murder and kidnapping to adultery, blasphemy, and witchcraft. The Code of Hammurabi, which came even earlier than Moses, contained similar penalties.

In the Roman Republic, and later the Roman Empire, death was also a common punishment. Arson, treason, and piracy were all punishable by death, and one’s social class often determined the method of execution. Roman citizens could be beheaded, which was a quick and relatively humane death compared to crucifixion or being mauled in the arena. The Apostle Paul, a Roman citizen, lost his head, while the Apostle Peter was hanged on a cross.

In medieval Europe, common criminals were usually put to death by hanging, while nobles condemned to death were beheaded. The original purpose of the guillotine, in addition to allowing the French Revolution to kill on an industrial scale, was to equalize death—nobles and commoners alike were executed in the same manner.

Compared to today, when many states refuse to impose the death penalty at all, and in those that still do it is rare and preceded by years or decades of legal proceedings, the pre-modern world regularly used execution to punish crime. Criminals were not considered misguided souls who made a mistake and needed an opportunity for atonement; they were threats to civil society that, if left unchecked, could disintegrate civilization.

Whether the offenses were considered crimes against God or crimes against social order, the outcome was the same: crime eroded society. If criminals are allowed to harm their neighbors with impunity, society becomes unable to function properly. The Apostle Paul, despite undergoing persecution by the Roman Empire, still explained in his epistle to the Romans that governments were instituted by God for just purposes.

Consider El Salvador, which just a few years ago had the highest murder rate in the Western Hemisphere. Shopkeepers conducted business at the mercy of vicious gangs, and innocent people were often brutalized for no reason.

Nayib Bukele was elected to office in that country and set to work dismantling the gangs and imprisoning their members. His methods were denounced by American leftists and international NGOs, but they worked. Today, El Salvador is one of the safest places in the world. It turns out that solving crime can be as simple as locking the bad guys up.

Of course, that raises the question: how do you know who the bad guys are, and do you trust those who say they do?

When America was born, she inherited a system of crime and punishment that had evolved in England over many centuries. In Anglo-Saxon times, crime was often handled privately, with blood feuds carrying on for generations. Saxon kings attempted to crack down on such threats to public order by codifying laws such as the weregild, a price that a murderer had to pay the victim’s family depending on the victim’s social class.

The concept of a jury developed around the same time, when justices would call members of the community to testify to the character of the accused. Later, juries became concerned with the facts of the case rather than character alone.

By the time of the American Revolution, both England and the colonies prescribed capital punishment for many crimes. Jails and prisons were expensive, so it was simpler to either punish a petty criminal through whipping or a day in the stocks and then release him, or put him to death. We have become conditioned to see execution as cruel, but our ancestors saw it as necessary to maintain social order.

While modern society emphasizes rehabilitation, our ancestors believed in physically removing dangerous elements. Are we more enlightened now?

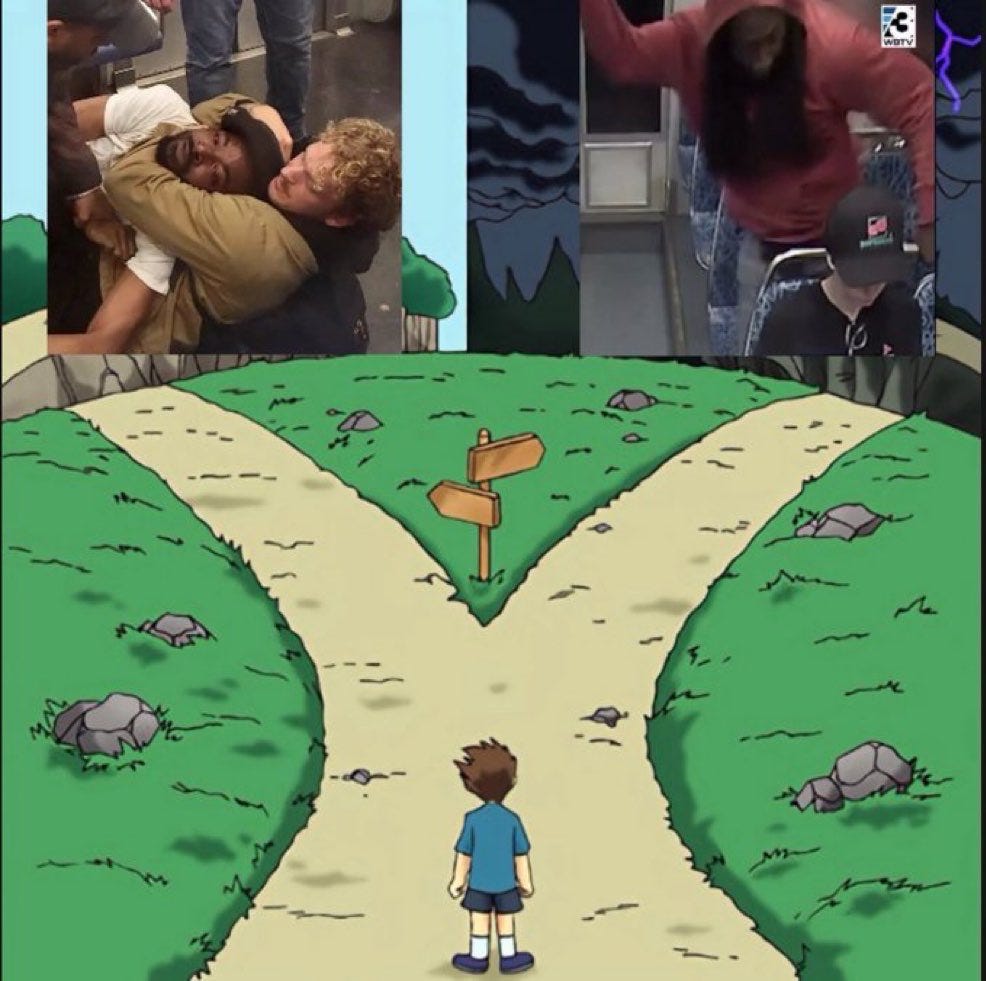

I bring this up as context to a horrific crime that occurred recently in Charlotte, North Carolina. A man with 14 prior arrests was riding behind a young woman on a metro car when he pulled out a knife and stabbed her in the neck. The entire incident was caught on video. The victim, Iryna Zarutska, is a Ukrainian refugee who came to the United States to escape the Russian invasion of her country. Consider the implications of an urban American metro being less safe than a literal war zone.

Why is this the case? How did things get so bad?

America has forgotten the idea of justice. Our ancestors knew that criminals must be punished and that threats to social order must be removed. Today, we have it backward. We have come to believe that justice is served by not punishing criminals, and our compassion is directed not to innocent victims but to the perpetrators themselves.

DeCarlos Brown Jr. was not a productive member of society. He repeatedly ignored the law yet faced no meaningful consequences. A person like that would have long ago been incarcerated or executed in past societies, but in America today he was free to commit murder. The magistrate who released him most recently, Teresa Stokes, is not a lawyer—she apparently never passed the bar—but has the responsibility of deciding the fate of criminals in North Carolina. She is also the director of operations for Second Chance Services, a mental health and addiction clinic in Charlotte.

Is there a conflict of interest in a magistrate who releases criminals that could then potentially be taxpayer-supported clients of her firm?

The racial angle of this crime cannot be ignored. We are often told that, rather than real justice, which punishes the guilty and protects the innocent, racial justice requires leniency for black criminals to balance the scales against slavery and Jim Crow. In 2020, America experienced a summer of riots, billions of dollars in damage, and dozens of deaths in response to the death of a career criminal in police custody. Even many Republicans attended George Floyd’s funeral, featuring a golden casket, while ordinary Americans were told to stay home and mask up.

Will there be riots in the name of Iryna Zarutska? Will governors and senators kneel before her golden casket?

According to Meg Basham, the left-wing MacArthur Foundation gave Mecklenburg County a $3.3 million grant intended to reduce the jail population in the name of racial equity. Ironically, this push for racial equity may have caused additional harm to innocent black Americans, since black-on-black crime occurs at a far higher rate than interracial violence. By treating black criminals with kid gloves, we make conditions worse for those trapped in violent neighborhoods who genuinely seek the American dream. As President George W. Bush called it, we risk succumbing to “the soft bigotry of low expectations” by assuming crime in black neighborhoods is simply a fact of life.

Indeed, we are told that rampant crime is just part and parcel of life in 21st-century America: that being assaulted, robbed, carjacked, or even murdered is an unavoidable part of living in big cities. Democrats protested when President Donald Trump used his authority to mobilize the National Guard to fight crime in Washington, D.C., seemingly more outraged at the crackdown than at the crime itself.

Crime is treated like a force of nature, something we must simply live with, rather than a deliberate policy choice. It’s not as if America lacks the resources or the willpower to address crime—after the unauthorized tour of the Capitol on January 6, 2021, the FBI and other law enforcement agencies devoted immense effort to investigating everyone who was anywhere near the building, arresting hundreds who simply walked through open doors.

Or consider the charges filed against a young mother named Shilo Hendrix, who was caught on video saying the forbidden “N-word.” In our upside-down world, a white woman saying that word is treated as more serious than murder, on the level of blasphemy in ancient Israel.

The way we treat crime in America today is disturbingly similar to what Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn observed in the Soviet Union. In The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn wrote:

…your punishment for having a knife when they searched you would be very different from the thief's. For him to have a knife was mere misbehavior, tradition, he didn't know any better. But for you to have one was "terrorism."

Had Iryna Zarutska been caught carrying a concealed pistol on the Charlotte metro, she likely would have faced the full force of the law. Meanwhile, her murderer, DeCarlos Brown, was released fourteen times. Recall that Marine veteran Daniel Penny was chared with murder in New York City because he killed a man with a chokehold on the subway who was threatening to kill innocent passengers.

This same phenomenon is occurring throughout the Western world. Native English men and women often face harsher punishments for posting unauthorized ideas on social media than migrants who rape children. Justice has been perverted, running exactly contrary to our common law ideals. Rather than a blind search for the truth, the focus has shifted to “who” is doing what to “whom.”

High crime is a policy choice. The streets of New York City were once incredibly dangerous, inspiring films such as Death Wish with Charles Bronson. Citizens eventually got fed up, electing Rudy Giuliani as mayor. He promised to clean up the city, and he did just that. Yet his methods, like Nayib Bukele’s in El Salvador, were criticized for pushing the limits of civil protections. Over time, people forgot why Giuliani was elected in the first place, returning to leaders who were soft on crime. Current mayoral frontrunner Zohran Mamdani has promised to empty the prisons if elected.

Hard times create strong men, strong men create good times, good times create weak men, weak men create hard times. We forget this maxim to our own detriment.

Another recent event illustrates the same tensions. President Trump ordered the destruction of a boat allegedly carrying drugs from Venezuela in the Caribbean Sea, drawing criticism from leftists as well as libertarians like Sen. Rand Paul. In response to Vice President J.D. Vance tweeting, “Killing cartel members who poison our fellow citizens is the highest and best use of our military,” Paul cited the 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird as a caution against extrajudicial killings.

Many conservatives roasted Sen. Paul’s statement, pointing to historical precedents such as President Thomas Jefferson’s actions against the Barbary pirates. This is where first principles collide with the real world: what is the libertarian answer to foreign nationals smuggling deadly drugs into our country? What is the libertarian response to unchecked crime in American cities?

If Rand Paul was president of El Salvador, instead of Nayib Bukele, would the citizens of that nation feel safe walking the streets at night, or would they still fear for their lives? Libertarianism is a luxury belief that can only exist atop a civilization where wrongdoers are punished and innocents protected.

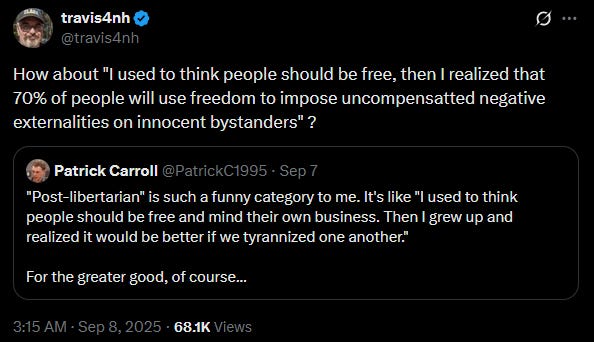

State Rep. Travis Corcoran of New Hampshire, a great libertarian voice of reason, responded to discussions of “post-libertarianism” with a reminder that most people will not follow the non-aggression principle on their own:

As usual, Corcoran’s whole thread is worth reading. The libertarian ideal of government leaving us alone to live in harmony only works if human beings are inherently good. If you reject that premise, recognizing that humans will often choose to do wrong, it follows naturally that society needs methods to enforce the law and maintain order.

I’m sure Sen. Paul would insist that alleged drug traffickers be captured and tried in court. “Due process” is the cry we continue to hear from Democrats and libertarians alike—applied to drug traffickers, illegal aliens facing deportation, or other cases. But what exactly is “due process”?

The Founding Fathers were so concerned with due process that five of the first ten amendments protect citizens in the legal system. They knew how kings and dictators of the past had abused the criminal justice system against political enemies. The Court of the Star Chamber, created to allow the King of England to bring justice to those persecuted (or shielded) by local magistrates, quickly evolved into a tool for persecuting enemies under color of law.

The Fourth Amendment prohibits law enforcement from searching your property without a warrant.

The Fifth Amendment requires indictments by grand juries, protects against self-incrimination, and prevents double jeopardy.

The Sixth Amendment guarantees a speedy trial, jury trial, confrontation of accusers, and legal counsel.

The Seventh Amendment preserves the right to trial by jury in civil cases.

The Eighth Amendment prohibits excessive bail, excessive fines, and cruel or unusual punishment.

Those last phrases have provided the basis for many soft-on-crime policies today. What is “excessive” bail? What is “cruel or unusual” punishment? Is execution cruel? I don’t think it should to be pleasant, for sure. Executions were once carried out publicly, both to deter potential criminals and to demonstrate justice. Today, the death penalty—rarely applied at all—is conducted in antiseptic conditions, with lethal injections administered quietly by medical personnel.

Idaho recently designated the firing squad as the primary method of execution, though it has not yet been used. Personally, if I was facing that situation, I would prefer to die standing on my feet than strapped to a gurney and stuck with needles.

Matt Walsh pointed out that criminals should not enjoy comfortable punishments:

These days we try to find ways to punish criminals without making them suffer. We make prisons as comfortable as possible. We’ve done away with hard labor. Even executions are supposed to be “painless.” This is the problem with our modern justice system. The whole point of a punishment is to cause suffering. There is no punishment without suffering. That’s literally what makes it a punishment. We should be inflicting punishment on criminals intentionally. Make it hurt. Make it painful. Make them suffer dearly. This sounds brutal and cruel to modern ears only because we don’t understand the fundamental point of anything anymore.

In our quest to avoid “cruel and unusual” punishment, have we gone too far, making life too comfortable for those who break our laws and threaten social order?

At the time of our founding, “due process” meant a speedy trial and immediate punishment. Today, it often means years of motions, appeals, and delays before a trial is completed. Capital punishment can take decades to carry out—often those who are executed today committed their heinous crimes 20–30 years prior.

Is that the only option for criminals like DeCarlos Brown Jr. or foreign nationals trafficking deadly drugs? Would Sen. Paul have demanded due process for enemy soldiers on a battlefield? Is there a difference between a declared war and the asymmetric conflict between law enforcement and criminal networks? Should Congress declare war on drug cartels? How about career criminals?

I don’t have pat answers to these questions.

I came across a graph on Twitter showing the percent of people arrested by how many previous arrests they had. It wasn’t sourced, so take it with a small grain of salt, but I know I’ve seen it before:

Most people in America are not criminals, and most crime is committed by people who have already committed other crimes. As Nayib Bukele demonstrated, solving crime can be as simple as locking up repeat offenders. Someone like DeCarlos Brown, with 14 prior arrests, should never have been on the street with the ability to murder an innocent woman. He should have been locked away for life, at least.

In the 1990s, President Bill Clinton supported a “three strikes” policy: after a third violent felony conviction, the offender would be imprisoned for life. Critics cited exceptions and potential racial disparities, but the alternative was allowing repeat offenders to assault, rob, or murder freely. Clinton later denounced his own bill, claiming it only made the problem worse. Did it? Or did the Democratic Party simply shift priorities away from protecting Americans over the past 30 years?

These questions are not purely academic for Idaho. We face the same temptation to go soft on crime, to make prosecution harder, and to assume people will act rightly without social and legal enforcement. Misplaced compassion led Idaho Democrats to argue that vagrants have more right to city parks than law-abiding citizens—a path that leads to tent cities like those in Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco, along with the drugs and crime they inevitably bring. Many families now avoid neighborhood parks in major cities for fear of crime. We don’t want that here, yet Sen. Codi Galloway was lambasted and even threatened for carrying a bill to prohibit vagrancy.

The “broken window theory” is true: if you let small crimes go unpunished, criminals will soon commit larger crimes with impunity.

As longtime readers know, my position has never been to give law enforcement unchecked power. During the 2024 legislative session, I raised concerns about a bill to create mandatory minimum sentences for fentanyl possession and distribution. Laws and those tasked with enforcing them require careful oversight to protect our constitutional rights.

At the same time, we cannot go too far in the other direction. We must reexamine the pro-crime policies that allowed the death of an innocent woman in Charlotte and determine how to protect Idaho citizens from a similar fate. While we were raised to view hangings and beheadings as barbaric, our ancestors might call us the barbarians for allowing repeat offenders to walk free and kill without consequences. How did we get to the point where Mayor Vi Lyles of Charlotte expressed more compassion for the murderer than the victim?

Conservative Christian commentator Allie Beth Stuckey said it well:

America failed this girl. We protect criminals. We glorify degenerates. We have no will to restrain evil, no courage to punish wickedness. We sacrifice the weak on the altar of social justice and pat our backs in the process

Stuckey recently wrote a book explaining how “toxic empathy” can twist virtue into support for criminals at the expense of victims. In another tweet, she said this murder is precisely the result of empathy turned toxic:

“How can empathy be toxic, Allie?”

Well, you see, this animal was arrested and released a dozen times in the name of social justice and racial equity. Social justice and racial equity policies are borne out of “empathy” for the “marginalized.”

Bad actors convince well-meaning, compassionate Christians that these empathetic “restorative justice” measures are the right way to love our neighbors.

In this way the criminal becomes the victim, and society becomes chaotic and disordered.

Be led by truth, order, love, goodness, and virtue, not empathy.

High crime is a policy choice. If we want any hope of a functioning society to hand down to our posterity, we must punish wrongdoers, remove career criminals (sad that this is even a phrase in our language!) from the streets, and protect not only our constitutional rights, but also our life, liberty, and property.